I will be heading back to Colorado soon for the final phase of my father’s earthly life. The timing is still up in the air, but soon, is clear. Colorado has an 8-hour time difference from Berlin, so there’s the jet lag to deal with, plus the altitude. Denver is 5280 feet or 1609 meters above sea level, and, being the sensitive soul that I am, I need a while to adjust to altitude and time differences, too. Forget driving up the Rocky Mountains within a week of arriving, I tried that once and just laid in the back seat, trying not to lose my lunch.

The mountains are beautiful, but not my natural habitat. I also learned that during my trip to Tajikistan, whose topography resembles Western and Southwest US areas. Boulder, Colorado is even a sister city of Dushanbe, with its own genuine Tajik-Teahouse, which I made a point of visiting once.

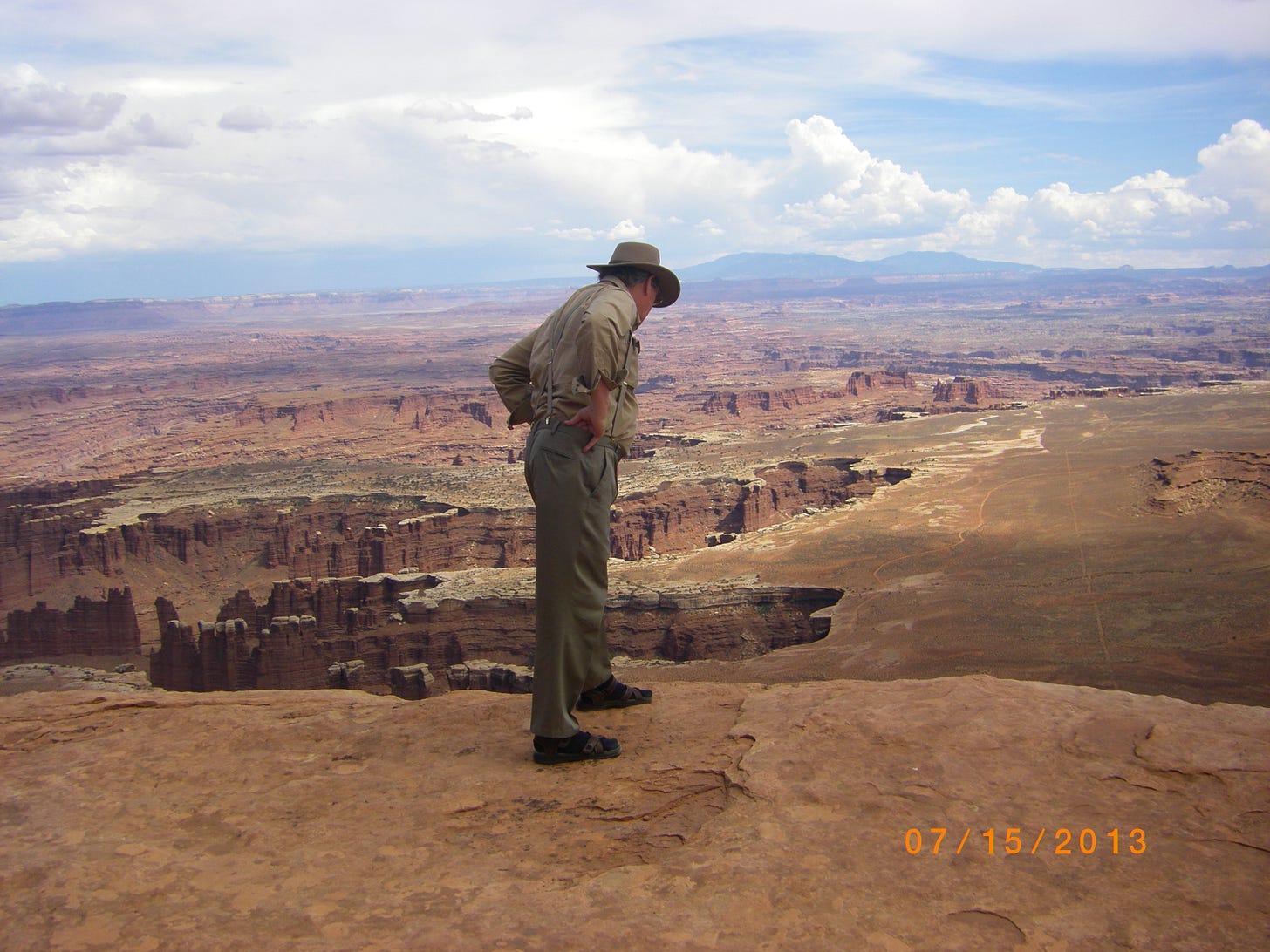

My father loved the mountains. He studied and even taught geology throughout his life and loved to bring guests on trips to the various parks and sights in Colorado, Utah, Arizona, and beyond. Here he is over ten years ago when we went on a road trip to Moab, his favorite national park.

Now for a look back to the Mountains of Tajikistan and how I got to see them up close with my study abroad program in 2010.

The Pamirs in October

Our driver’s name was Norula. For some reason, it took me the whole week to remember this without having to check my little notebook, where I tried to jot down my thoughts and some facts along the way. In the first ten minutes of driving, Norula had already put a wad of nass (a nasty stinky green powdered form of chewing tobacco cut with lime, which Tajik men spit everywhere) into his mouth to fuel the driving focus and when he spit the juice out the window, and it blew back into my window and landed on my face—I knew it was going to be an interesting trip.

Norula had huge, hairy hands with thick red and worn fingers with which he gripped the steering wheel as we came within inches of hurtling off the edge of the dirt road and down a sheer cliff into the Panj River below. Though not very pretty, Norula’s skillful hands were the key to our survival. I have forgotten now even how many times it seemed we cheated death. Later, we heard that some Tajiks had all died the week before when their vehicle suffered that very fate, hurtling off the road into the ravines below.

Starting out at six in the morning from Dushanbe, it took at least an hour to get out of the city due to being stopped by the police. Our caravan of three cars was trying to stay together, and usually, the police would pull all three over. The ritual of counting the bribes began. The lead jeep was driven by Gholebnazar, a native of the Pamirs—the people on the losing side of Tajikistan’s civil war in the 1990s. Like his fellow Pamiris, he looked more European than Russian or Asian, like the people in the rest of the country and Dushanbe (including the rival Kulobis, where the President of Tajikistan and his winning coalition are from). This meant that Gholebnazar’s car was pulled over almost ten times before we got far from Dushanbe on the road east towards Kulob—likely due to his appearance. It evened out eventually when we got to the Pamirs, and then it was the other driver’s turn to be profiled.

Ultimately, money speaks louder than any tribal or regional affiliation these days in Tajikistan—and the sight of our well-equipped and well-heeled jeeps was probably the cause of most of our police checks and subsequent bribes. The drivers were responsible for negotiating their own bribes, so when Norula came back to the car after each police visit, our other traveling companion, Jamshed, the handler, would ask: “How many Somoni did he get from you this time? Norula would sheepishly say, 1 or 2 Som. It was never more—until later, when it took ten Somoni to recover from the police seeing someone jump on the back of a jeep for a short ride and acting very offended that this be done in front of them.

We headed east through Kulob on our first day. Norula had obviously mastered a special yoga driving position that enabled him to go 12 hours without tiring: shoulders loose, arms relaxed, back at ease, and eyes focused intently upon the road. He had been driving professionally for over 15 years. The third driver was Zafar, an intelligent man with the mischievous and confident nature of someone who knows his place in the world. He had been a prison psychiatrist, and when the danger of contracting tuberculosis and giving it to his family became a real possibility, he quit the prison and became a for-hire driver.

The road was truly atrocious. There would be short stretches of sanity, but mostly, it seemed like the entire country was under some kind of construction, with the roads being the main focus. They didn’t have any type of road construction signs or markers to warn you except sometimes rocks would be piled into neat little stacks to indicate a divider (what would be the point even, the whole country would be covered), so driving along, we’d suddenly swerve wildly around an impromptu detour where a bridge was out ahead, and if the driver hadn’t been watching we would have hurtled off the end of the road. We passed some Chinese road construction crews—wearing the old-style stereotypical pointy-Asian hats. We were told that the rumor was that these Chinese laborers were actually prisoners and working in conditions that not even Tajiks would tolerate.

For twelve hours of driving the first day, we listened to the multimedia disks that our driver had brought along—and then started listening to them all over again. “Voyage Voyage!” (by Desireless, this French Euro-pop song is currently very popular), “You're In the Army Now” (by Status Quo). When we turned a corner and descended from a small pass and laid eyes on the Panj River valley below and—for the first time, Afghanistan across the river—The Scorpions’ “Winds of Change” was blasting from our jeep’s speakers and will forever mar my initial memory of Afghanistan.

We passed donkeys, baby donkeys, herds of goats and sheep, dogs, cats, and cows. Cows in the narrow fields, cows on the roads, cows on the hills, cows in the driveways with skinny children herding them using long, thin sticks. We passed wild pomegranate and pistachio trees and crossed a flooded river bed where the bridge was long gone, and it felt like a roller coaster ride to get to the other side, our heads and legs banging against the sides of the jeeps as we careened over gulleys and across a very scary narrow sheet-metal bridge. We were rewarded on the other side with village children selling pomegranates and chocolate persimmons. Delicious.

By the time we reached our lodging for the first night in Qalaikhumb, we had been stopped and passed through innumerable fixed border and completely arbitrary local police, border guard, and military checkpoints. I lost track after the first few stops, where the lonely and bored men in uniform would sometimes just call the drivers to come give bribes in the privacy of their trailers or maybe come open the doors to our jeeps and demand to see our passports, but not before getting a good eyeful of the women in our entourage first.

We stayed at the Aga-Khan Foundation-supported guesthouse “Darvazeye Badakhshan” where I went to sleep with the sound of the Panj River roaring past. The next day, we continued toward Khorog, the capital of the Gorno-Badakhshan region. We stopped without explanation in a town called Rushan, where some members of our party disappeared into a house, apparently in search of black market garnets and rubies. They came back empty-handed. We stopped for lunch at a sort of rest stop. There was a restaurant and a bathroom from hell. The little hut at least had a mens and womens’s side, but the hole in the floor and the accompanying breeze and flies made me prioritize my bodily function needs. Like the perverse reversal of the fairy tale line about each sister being more beautiful than the next, each toilet situation we came across was more disgusting than the previous one. What I came to prefer was a boulder beside the road.

In Khorog, we stayed at an Ismaili Center Guesthouse (featured in the Lonely Planet guide). The put us ladies up in what seemed to be their private home, with our own bathroom and shower (though the water situation remained mysterious and involved some Gerry-rigged septic and plumbing apparati). The males slept in the main guesthouse dorm building under construction, and I was glad for the small privileges of our gender when the temperature got down into the low 40s that night. We had dinner at the Khorog branch of Delhi Darbar Indian Restaurant, and it was a very welcome change from the Tajiki staples of oil, meat, potatoes, carrots, and rice.

Walking back to the guesthouse in the pitch dark, the stars were unlike anything I have ever seen in my life—even compared to Colorado—the starriness of it all here was immeasurable. The Milky Way was indeed milky and took up one-third of the sky. The next day, we had tea, bread, and jam for breakfast and were on our way again eastward through the Wakhan Valley corridor towards Ishkashim.

First, we stopped at the Afghan market. The Afghans come across a little bridge with their wares—traditional hats, scarves, fabrics, CDs of Afghan music, and other cheap crap. While we were in the market, gawking and being gawked at, someone stole the Toyota insignia off the top of our jeep. I started to understand the paranoia of our drivers—they had slept in their vehicles the night before.

When we got to Ishkashim at five that evening, I felt like it was 9 pm; I was so tired. The sensory overload from the day caught up with me. The mountains were immense, the remoteness truly palpable. The constant police and military presence all contributed to an incredible feeling of vulnerability. We passed several police checkpoints, and border guards were on patrol along the roads; these soldiers definitely drew the short straw when it came to assignments. Another task I’m sure they were in charge of was painting the words “Vahdat” that is, “Unity” all over boulders on the sides of the roads. These white, hand-drawn markers of a central government desperately trying a little too hard to create a sense of unity where none existed was sort of sweet. Every town we came upon also had painted signs saying “Khosh Amadid” or “Welcome.”

Once, when we got out to take photos of an Afghan village, complete with donkeys carrying bundles of sticks, villagers in colorful garb, and mud and stone houses just across the river, a car full of police or (former) KGB officers stopped and told us we were not allowed to take photos. Later on, we heard shots ring out when we passed a police checkpoint, but they told us they originated from our side of the border. This place was very far from home. What if we ran out of gas? What if more than two tires busted? We only had two spares. We saw plenty of unfortunate vehicles marooned on the side of the road.

When we arrived in Ishkashim, the guesthouse had a wonderful hot shower, and we ate goat meat soup and watched Afghan television for the first time. The town of Ishkashim was remote—but they had an Internet cafe! We met a woman on the street who spoke excellent English and told us she worked for the Aga Khan Foundation-supported Micro-Finance bank, which had funded the start-up of almost all the businesses in the town, including the Internet café.

The next day, we continued eastward and stopped at an Ismaili shrine and a little local-run museum about the history and people of the Wakhan Valley. The curator played a guitar-like instrument and sang for us in the Wakhani language. The next stop was the Bibi Fatima Zahra holy hot springs. They were overrun by French people associated with the filming of a movie called “Special Forces” about soldiers in Afghanistan. Apparently they had decided that this town would do as the location for their fictional Afghan scene—a town across the border in the mountains across from the actual Afghanistan. They had asked the locals to grow their beards out months in advance and provided them with Afghan dress, so the whole town had a strange non-Tajik look to it. The hot springs were indeed incredible, and I felt like I’d been reborn after only being able to stay for ten minutes in the steaming hot water. The complex was set in a gorge where a river came rushing down, and there was a building over the hot springs where you could change before sitting in the surreal cave with the hot water pouring through and under the stairs; the river rushed by below. It was a beautiful scene, with an ancient fort, windy roads up the mountain past villagers bent over threshing the wheat in their little plots of land by hand or with oxen—then standing up to answer their cell phones.

We continued on our way to the most remote spot of the Pamirs—a village called Langar, which consisted of a few houses and a little store, two of the houses serving as guesthouses for tourists like us. We could see the mountains of Pakistan in the distance, and again, the stars were breathtaking. They had a small generator for the lights to see our dinner (mutton soup and Polov), but then when the lights went out, our headlamps finally came in handy—to find our way to what passed for an outhouse behind the house; this was a hole in the ground, surrounded on three sides by some tarp, and with a garbage can for the used toilet paper. It’s hard to relax when you have a cold breeze on your bum. That night, it got colder, and the winds kicked up; I was glad I brought my high-speed, lightweight sleeping bag. We were all very grubby in the morning and had that dirty camping feeling. The wind had strewn the poopy toilet paper across the bushes and trees nearby.

It was time to turn back via the road north, through the Hare Pass (14,450 feet) looping back to Ishkashim, and tracing our steps back to Khorog, Qalaikhumb, and then back to Dushanbe. The highlight of the return was our stay at the Ismaili Center in Khorogh again; some of us got to sit in on a prayer service at the Jama’at Khanah Mosque; the Ismailis are a sect of Shia Islam, a minority in the country. The men and women sat and prayed together, and a man and a woman led the prayers. In the rest of mostly Sunni Muslim Tajikistan, women are not even allowed into mosques.

After suffering four weeks of serious intestinal issues in Dushanbe, I had a week of perfect health and happiness in the Pamirs, and I do hope to return to do the place a bit more justice. The people we met were incredible—hospitable, kind, generous with their time and laughs, and when they spoke Tajiki, I could understand them better than the Dushanbe dialect.

If you’ve enjoyed my series on Tajikistan, last post here, consider subscribing and sharing with your friends and network.