When my father died, I was on a plane somewhere over Indiana or Missouri, watching Season 2 of “And Just Like That,” the Sex and the City miniseries revival. We were delayed for at least an hour, making a big loop around a storm over the Midwest, so I turned on the TV.

I knew it would be intense when I landed, whatever state he was in, so I decided to zone out a bit—at that point, it was after midnight Berlin time, and my brain was fried. My sister and brother were helping my stepmom take care of my dad, and I had heard that he was suffering greatly, not just the cancer pains but due to delirium. I was thankful that they were there and not me.

When I said goodbye in February, I was crying all day and not particularly helpful. During that visit, I did manage to help get the oxygen machine hooked up and do things like fetch medications and water, but I couldn’t turn off the tear spigot. I knew I was going to be more helpful afterward.

The phrase “for the duration” came up in February when we discussed how long my sister, a doctor with geriatric specialty training, would return to help. Although she had many other familial responsibilities, she was there for that long duration.

During Covid, when the miniseries came out, even I heard that Mr. Big had died suddenly at the beginning of the show. But because the airline only offered Season 2, I was spared that dramatic scene also. I began watching where our widowed heroine, Carrie Bradshaw, has already written a book about the traumatic experience and her grieving process. Now she’s getting ready to give a reading at “Widow-Con” to a packed hall full of widows. I shed a tear at that scene, one of the few ones I could relate to, in between shi-shi lunches where the girlfriends are bedecked in more accessories than I own, and Ms Bradshaw drops a check for $100k for a charity yet refuses to discuss bodily functions and aging for an ad on her podcast.1

When I got off the plane, my stepbrother told me that my father had died six hours before. I could only say, Oh. Okay. My mind was a blur from jetlag, and it took us a long time through Denver traffic to get to my father’s home. I had some time to adjust my expectations of the next days to fit the fact, but when we arrived and the family was waiting, I was glad to be able to see and touch his still-warm body to make it real. The waterworks began, and the relief surrounding him and everyone who had been sitting with him for days was palpable.

That week in Denver was like existing inside a clock itself. We measured time in minutes and then hours since his death. The intensity of each passing moment sustained me to stay awake that Thursday, 25 April, until 8 a.m. the next day, my German time.

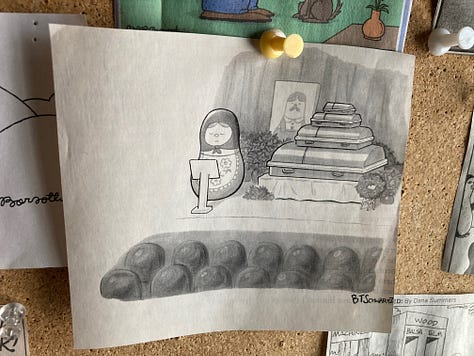

There was a vigil with the body from Friday to Monday in the chapel of his church. The community signed up for hourly reading slots from 7 am until midnight; I read to him from the books of the Apostles for an hour on Saturday night after it had snowed all day. Tall candles surrounded the casket, and the light glinted off his glasses—his most essential accessory. I read aloud, stopping to wipe tears away.

Sunday, the community came for the service, and he was there, lying in repose. I could feel the meaning of that word, even as my tears welled up every couple of minutes. The words of the service have never been so intense.

Monday, we closed the casket with the first part of the funeral service and wept together. Then we walked outside to the flowers, sunshine, and laughter as they wheeled the casket into the awaiting hearse. We stood around talking, feeling the intensity of the spirit shining so brightly.

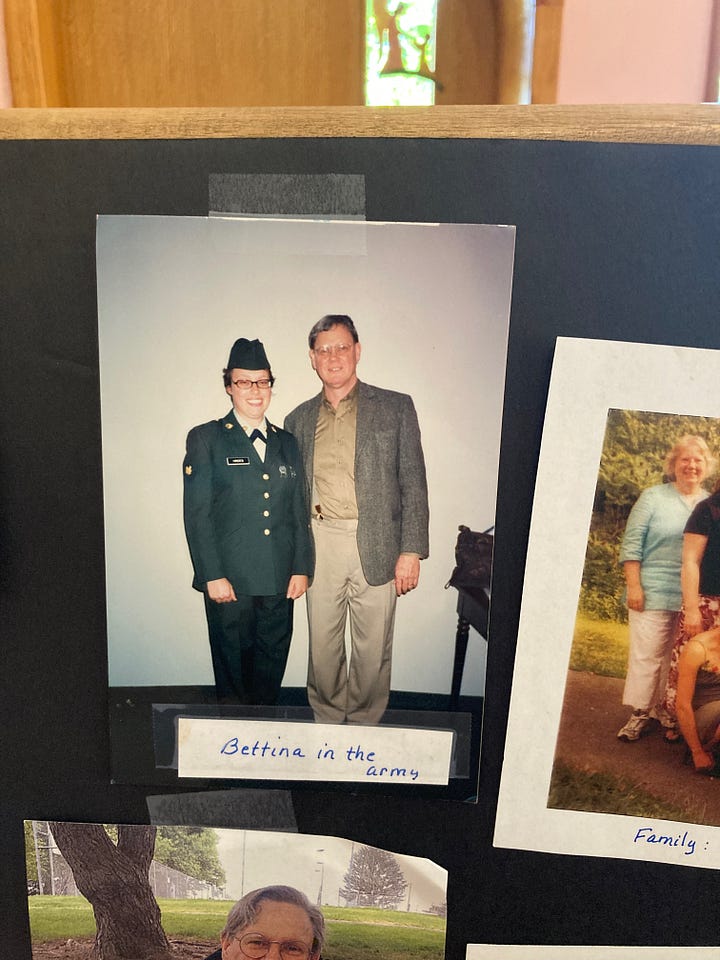

The next day, Tuesday, was the funeral—my new favorite sacrament—and the memorial gathering. Family and friends came from distant states, and the program, which my dad had carefully selected with photos and Bible quotes, was handed out. By then, I was tired of crying, so there was more laughter proportionally.

The house was filling with flowers, sent from all over, and the beauty and aroma helped with the grief. Our family sat at the kitchen table sorting through his “Humor” folder, where he kept all the comics that rotated on/off the bathroom wall, laughing and sharing tales.

By the time most people left on Wednesday, and his wife brought home the ashes in a big, heavy black box on Friday, it felt like it had been years and yet only a minute, but it had been a week. Now, it has been over a month since his physical death. And when you read this, it might be years.

I was expecting to be relieved when my father died. So much pain, suffering, and anticipation finally concluded. I wasn’t expecting so much laughter and joy to accompany his passing. His birth into the spiritual world was not an easy one, but the immense joy was that much greater as a result.

Some people were tiptoeing around me when I got home, not knowing how I’d deal with his death. But I felt like a confetti balloon had gone off in the spiritual world, and rejoicing was due. I tried to convey this to the people he left behind. Dying is a full-time job. He approached it as he did many things: intensely, deeply, and as meaningful work. So many people worldwide were sending their condolences, and one line stuck out that many posted on Facebook: “May his memory be a blessing.” The fact that this was the first time I’d consciously been aware of this phrase reveals how few deaths I have dealt with (at least in the English-speaking world). It sounded trite initially until I experienced the truth of it. His memory IS a blessing! I can hear an echo of his belly laughter in my soul.

Here are some of the words I spoke at the memorial gathering, after the photos.

Papa—that’s what we kids called him—loved flashlights; guess how many I counted in his house and garage? At least fifty! Flashlights and lanterns in every drawer, shelf, and corner—some battery-operated, other solar driven, both big and small—various makes and years. Mag lites, black lights, desk lamps, pen lights, closet lights, overhead lights for his many mineral and crystal displays, prisms, laser pointers, and magnifying glasses.

He needed to be able to see clearly, to have everything illuminated properly. My dad wanted to get to the bottom of things. From rocks to light, he wanted to understand the full spectrum of the material world as much as he strove to understand the world of ideas.

Besides the literally thousands of rocks, crystals, and minerals lying around on every surface, shelf, and special case, my dad also had tens of dozens of sticky notes, pens and paper types, fingernail clippers, chapsticks, eyeglass cleaner cloths and screwdrivers in every drawer. In between these, rubber cockroaches were placed on shelves or drawers to elicit the expected effect, and for a while there, the rubber chicken that would come out when the comic moment was right.

The contrasts were striking between the shelves of art books (especially French Impressionism) and his walls, which were covered with oil paintings from his talented twin sister and other artists he had met personally. He was a mix of high and low culture.

Papa loved reading and learning. The life of the mind, ideas, and concepts, he voraciously consumed books, acquiring many more than he could ever read. He would spend hours studying various levels of university-level mathematics and physics courses and even had a dedicated desk for it in the basement spare room. I remember wondering why he kept buying more books when he was in his late 60s. Doesn’t he know he will die before he can read them all? I thought. He had some primal urge, a thirst to acquire knowledge as if he’d been locked in a cage for the first half of his life and needed to make up for lost time.

Despite his professed love of abstract ideas, concepts, and all things intellectual, his true priority was personal relationships. He cultivated them through calls, letters, and visits around the world. He kept files of all the letters, cards, school grades, university essays, and other writings that we sent him from childhood onwards. He cared deeply about us and our development and learning.

As a father, he was always available and always wanted to keep the communication lines open. He had an agreement with us kids that if we ever found ourselves in a difficult situation where we felt unsafe, at a party or anywhere, we could call him, and he’d come to get us, no questions asked, no judgments. I think I might have been the only one who took him up on this offer, even calling from Italy in the middle of the night after a bad drug trip in my early 20s. He talked me down and helped me make it out of that situation. Papa was always available for us, for those he loved.

As a priest with five children, he was not afraid to ask people with means for money. For the church and a big parsonage. He asked and pursued a path to make the world accessible to his family and for his kids to have the opportunities he didn’t have as a child. He took on book translation jobs so he could afford to send us to Germany on exchange.

Later in life, when he was in the position to do so, he and his wife were very generous. Helping people they met along the way, especially young people with big dreams and nascent interests in the wider world and spirit, he would adopt them and make it possible for them to explore those dreams, be it Seminary or music or just trying to make it in a hard world. He was generous with his money and time, always there to listen, and received my letters over the years.

One of his favorite crystals was quartz. The omnipresent mineral, which he would quiz us on sometimes to see if we recognized it—could we identify which one of its many manifestations he held? I had forgotten the line he used to explain how to remember the chemical formula for quartz, but his colleague reminded me that quartz is silicon dioxide. Dioxide is there twice because it needs a friend. My father was that friend to so many people. Sticking by your side through thick and thin, maybe even when you wanted to go it alone.

This could also feel overbearing, and I long found his tendency to meddle and talk to anyone and everyone about his kids embarrassing. I was certainly not the only child to experience this, but as a teenager, I felt uniquely embarrassed. After all, he was my religious instruction teacher, and I was trying to be cool. Having a priest for a dad was not cool in the 90s.

After taking so long to find my own path and not feel like he was omnipresent in my life, I know that now he is there for me still, all the time when I am ready to ask, and not limited by space and time. He is there for everyone whose life he accompanied, supported, and loved.

There are two links I’d like to share:

The directors of the Seminary of my church have a podcast episode where they describe my dad’s funeral, in the beginning, to give another angle on the event.

I have discovered another great Substack writer, Andrea Gibson, a poet who writes about how her life has been transformed by terminal cancer; take a look.

Just ask me, I will tell all about it!

So good. I especially loved the flashlight section. I felt transported into Jim’s garage…talking with Bettina today, I felt you, dear Jim. So thankful for you and your daughter…